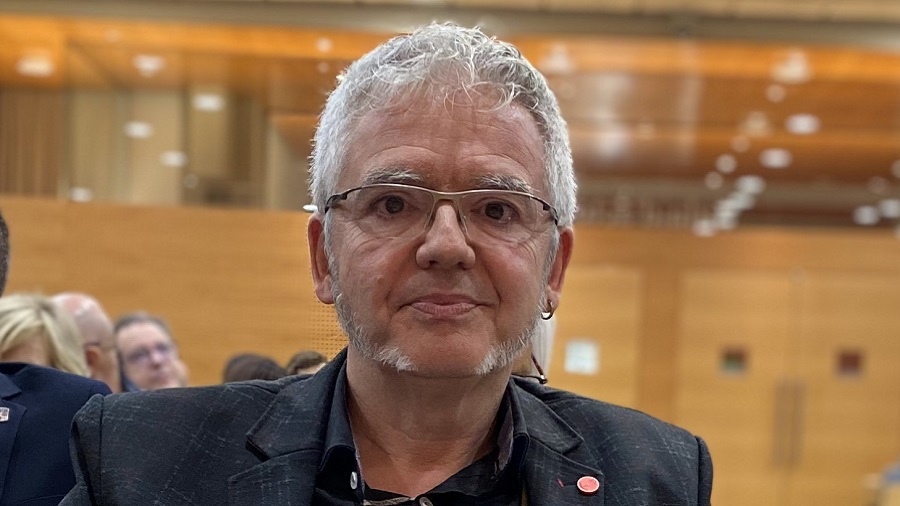

Màrius Serra: "Those using language to divide do not respect the language"

This year, the UAB dedicates its institutional campaign to showing its commitment with the Catalan language with the slogan "No em toquis la llengua" [Don't Mess With My Language]. During the institutional event inaugurating the academic year, the writer, journalist and member of the Language Section of the Institute of Catalan Studies Màrius Serra gave a speech entitled "Català, a l'atac en l'era del lingüicinisme".

I imagine that a love for word games and crossword puzzles begins with a habit of reading.

In general, reading regularly increases a person's vocabulary and, in my case, reading is closely related to pleasure. You read one thing and this leads you to read something else... And that is all connected to somewhat of a spirit of entertainment, a will to combine elements as if they were part of a game.

Have you always been a fan of crime novels?

I am an omnivorous reader, but yes, crime novels are part of my menu and I have always read them. They have extremely rigorous laws, just like a crossword puzzle. In other words, all sorts of things can be happening, but in the end, there must be an answer and everything has to make sense. Even in the more descriptive crime novels, such as those about Inspector Montalbano by Andrea Camilleri, and social ones, such as those by Petros Màrkaris.

Do you feel as if you were a disciple of Georges Simenon or of Georges Perec? Or are neither of them your mentors?

You are correct, although I am particularly fond of English-speaking writers. I have always read translations of Simenon's books. Not of Perec's, because the type of play on words he did formally made me want to read him in the original language. But my passion for experimenting with words is very much linked to narrative. In this sense, one of the writers who most inspires me as a reader and are a mixture of Simenon and Perec is Julio Cortázar in some of his works; he plays and experiments but never avoids using narrative, contrary to some of the more radical exploratory works of Perec.

In English, in the original version always, then?

Yes, I studied English and German Philology and I remember a big moment of enlightenment when I read James Joyce, particularly his book A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. When you signed up to do English Studies, ifrst you had to fill out a questionnaire and answer why you wanted to enrol in those studies. I said that I wanted to understand Finnegans Wake. [Laughs] Absurd, because it is an obscure novel where English is precisely the language that acts as a conductor to many other puns in who knows how many languages.

I imagine translations also have an entertaining component.

Translation in itself is the most profound reading that there is because you have to add a decoder to your target language. Some books are so fascinating that you feel like you want to translate them while you read them. It is a process of rewriting that can be compared to a creation ex nihilo, but with a subtle difference: you are not responsible for the initial stream, it is given to you.

Plus, according to George Steiner, the “language of Europe” is translation, its true lingua franca, acting as bridges between different cultures.

In After Babel, yes! Translation is a documentable and documented act of communication. If you think about it, sometimes we need to translate within one same language, and interpret different registers. Translation makes diversity clearer, because when you translate, you realise that there are no perfect synonyms. The act of translating always implies that you will say the same thing in a different manner, and that is very enriching.

Languages are something that unite us, not divide us.

Of course. Someone who uses a language to divide does not respect that language. In any situation where there is a conflict, if you sit down and analyse the ones using language as an attack weapon, you know they are using it to manipulate. They use it in the same way they speak of immigration or any other social hot issue.

Do you also think less and less people read nowadays, or is it a false topic like so many others?

Yes, I believe—although this is the opinion of a boomer—that people find it more difficult to read, with less time and less concentration. At the beginning of the digital era, one of the metaphores we used was the differentiation between the culture of a hunter and a fisher: patient reading, a contract a reader takes on with a text that puts everything around the reader on hold, or the bang, bang of going from one link to the next. Who knows, maybe we read more now, even if they are just tweets, but we are not paying as much attention. And it is done simultaneously with other activities, which makes it a bit dubious.

How would you descibe the situation Catalan as a language is in today?

I admit that I see a negative, even alarming, situation. The use of the language, from the view of sociolinguistics and social quality and attitude, is in a state of recession. I am optimistic, and if we analyse these past few years, I think we are in the midst of a pendular movement, but I am not completely comfortable with the situation we are in and we must keep our eyes on it.

What is your opinion on the Catalan spoken in media channels?

In general, the language used is poor. There is an urgent need for some type of academic or institutional work to be done, such as creating an observatory to guarantee the quality of the language used, because the media is crucial to what type of a language is disseminated. The influence that writers had in the mid-20th century, is the same as the influence of TV and radio hosts have today.

Is it possible for people to talk more, but not better?

Yes. The problem is that it is very easy to use a language as a political weapon. When you argue about the quality of a language with someone, most likely you will end up talking about other extralinguistic aspects related more to politics, society, gender, etc. This is very unpopular, but feminisms, for example, have turned the language into a battlefield that has led to its impoverishment, i.e., an ideological exhibition that does not make the language more fluid, or efficient, or richer. Arguing over words is easy, and language is a vehicle for unresolved conflicts.

What would you say to someone who is reluctant to conduct research in Catalan, for example?

We must be aware of the fact that English is obviously a necessity, Spanish is widely used, and in some areas it is essential to use German. The fundamental issue here is for there to be a dissemination of science in Catalan, essays in Catalan. Many of the most important Catalan scientists have conducted research in English, French, etc, and at the same time have shared their results in Catalan, as is the case of mathematician Ferran Sunyer, who is the father of many of the mathematical terms we use in Catalan. It is a question of attitude, common sense and not closing any doors. All languages add up.

What is your opinion about the UAB's campaign: "No em toquis la llengua"?

I find it great. We are always talking about saving ecosystems, species, cultures, etc. And some of our actions, done to avoid conflicts, are leading to the recoil of a language with a longstanding tradition in Europe. We are one of the most important cultures to exist in Europe since the time of Ramon Llull. I find it extremely positive for a university to stand up and say “don't mess with my language” and value its language for what it is.

The UAB, with Sustainable Development Goals

Quality education