“The main sources of and means of exposure to the contamination we have inside our bodies are food and its packaging, what we drink and breathe, and lastly our workplace”

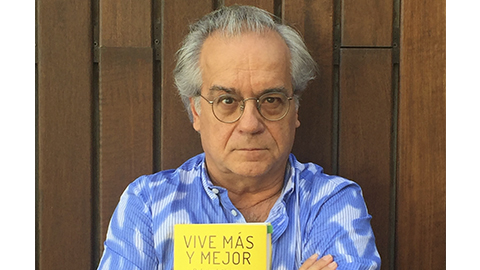

Interview with Miquel Porta, UAB graduate in Medicine and professor of Preventative Medicine and Public Health.

On 3 April, as part of the UAB’s Healthy and Sustainable Week, Alumni UAB invited him to give the talk “Our Internal Contamination: Food, Health and Society”.

20/06/2019

Miquel Porta, UAB graduate in Medicine and professor of Preventative Medicine and Public Health, is an expert of evaluating the impact of persistent toxic compounds (PTCs) and other environmental chemical agents on human health.

He holds a PhD in Medicine and a Master’s in Public Health from the University of North Carolina. He is currently head of the Clinical and Molecular Epidemiology of Cancer Unit at the Municipal Medical Research Institute (IMIM).

On 3 April, as part of the UAB’s Healthy and Sustainable Week, Alumni UAB invited him to give the talk “Our Internal Contamination: Food, Health and Society”.

We talk with him about his academic and public career, about the toxins present in our body and about the individual and collective actions we can take to live in healthier environments.

Why did you decide to study Medicine, and what was your experience at the UAB like?

It was one of the degrees I was considering, as well as Journalism and Sociology, perhaps all three because of their humanistic and social dimensions. I think that when I was 16-17 years old, these last two degrees were difficult if not impossible to pursue in Barcelona because of the Franco regime’s iron-fisted control. At that time, it was common to have to decide at 16, and many of us started university at the age of 17. The experience was great (it’s what I remember the most), but also very difficult (if I stop and think about it) because of the overcrowding. The prevailing feeling was lots of fun among friends. The UAB has improved immensely in these 45 years (I know that many of us appreciate it), but not as much as it should have: first, because the money that citizens have invested could have yielded more results; and secondly, because many universities in the world have improved more. I think that professors, students and administrative staff should demand more of ourselves, and those who work the best should be rewarded. It’s a moral, political and practical issue: if we don’t improve more quickly, the injustice and proletarianisation of youths will cause even more frustration, anger, populism, demagoguery, escapism and, yes, even more injustice.

You pursued a Master’s in Public Health from the prestigious University of North Carolina (UNC), where later you worked as a post-doc and professor. What did you get from studying in the United States?

Of all the universities that admitted me, I went to Chapel Hill, which I can largely “blame” on David Kleinbaum (a good professor), Joan Clos (a good epidemiologist and politician) and Michael Jordan (yes, the athlete). At UNC I found an incredible context and plenty of stimuli for learning, many of them intangible, immaterial. One particular pleasure: getting to the bottom of problems, thinking critically and creatively with no constraints whatsoever, connecting a wide range of public health issues, statistics and methodology, medicine, anthropology, environment, biology, politics… One day I mentioned a meeting with my advisor and he suggested that I write an editorial for the medical journal he edited: it left me paralysed! But I wrote it, with (secular) devotion, and even today it’s quite good. If we are self-critical (and not so “Catholic”), we should never be ashamed to say that we think a paper of ours is good. Instead, sometimes I suggest bold projects to professors here and they cower since they are used to a culturally stunted academic environment.

What was the start of your career like?

Much to my surprise, an outstanding professor, Joan-Ramon Laporte, who was wise, critical and demanding, offered me a job as a research fellow. At that time almost no one in society knew what this was, and the conditions were pretty precarious. Each generation has its own challenges… if it’s lucky. Joan-Ramon and my colleagues and I worked really hard, with critical and socially relevant critiques, we published, and we had fun. At the age of 24-25 I went to Minnesota and Massachusetts to study (for credit, taking the exams). With loads of excitement, effort and joy. Here, public health was either too ‘ideological’ and sterile or rather antiquated, or all of them at the same time. After three years as a fellow I won a scholarship from la Caixa to go to the USA. I was there three years, and then I was offered a job in Barcelona and came back. I’ve always worked with people from here and from around the world, and I’ve gone back and lived in Boston and New York. As the Josep Palau i Fabre poem says, “lucky he who has heedlessly crossed the sea and learned the world from one end to the other, who, obeying his wind, went with chance, which is the best country for motherless hearts”. To me it’s still my reality, my dream. I’d like to spend more time far away.

Did the return home go well?

Hard work and a bit of luck allowed me to come back at a time when the country and people like Pasqual Maragall and Jordi Camí were investing in research. It was a risk, because research is always critical, even more so in medicine. At that time, politicians and citizens were clearly focused on the important things: education, wealth redistribution, civil rights… issues with a real influence on our living conditions. One of the positive legacies of that time is that today there is good public health research in Spain. But those investments seldom reached the younger researchers.

One of your priority research interests is evaluating the impact of persistent toxic compounds (PTCs) and other environmental chemical agents on human health. And you recently wrote the book Vive Más y mejor. Reduciendo los tóxicos y contaminantes ambientales (Live More and Better. Lowering Environmental Toxins and Contaminants) (Grijalbo). What exactly is this internal contamination?

It’s the contamination we carry inside our bodies. The main sources and means of exposure are food and their packaging, what we drink and breathe, and then our workplace and lots of consumer goods: textiles, carpets, electronic products, cleaning and personal hygiene products… And there are even some toys that contain these substances.

It’s impossible to summarise the entire book, but what can we do to lower this contamination? What food and habits should we avoid? What can we eat and bring into our everyday routines? Could you cite several examples?

There are both individual and collective measures. Individually, don’t heat up food in plastic, and if you cook it at home to bring to work, let it cool off in a glass or metal container, and when it’s cool then put it in a container, which can be plastic. If you have to heat it up in a microwave at work, put it on a ceramic dish. These are both individual and collective behaviours, and agreement among institutions, companies and colleagues, family or school is often needed.

In terms of soaps, try to avoid parabens or phthalates, which are also found in many people’s bodies, and avoid triclosan in dentifrices. We should practice these habits consistently over time.

Why?

Because the most worrisome illnesses do not spring up from one day to the next; they are caused (or prevented) if we are exposed (or not) to toxic processes over the course of years.

What role does this internal contamination play in the illnesses we might develop? Is the upswing in some kinds of cancer related to it? Can we prevent it?

The range of illnesses is broad, spanning from infertility to congenital malformations in children (such as the genital-urinary tract), learning problems, allergies, autoimmune problems, type-2 diabetes, different kinds of cancer and even some cases of obesity, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer. The positive side is that we know a lot about these toxic effects, and many control policies have worked. For example, there has been huge progress in the external and internal control of lead.

Some toxins contribute to causing lymphoma, leukaemia and brain and liver cancer. We all have friends who didn’t smoke or have other kinds of harmful exposure but died of cancer. It’s true that the main cause of human contamination from cadmium is smoking, but it also comes from batteries, fish, partly from the industrial pollution of rivers and seas, and partly from the food chain. We need both individual and collective measures (as interrelated as they are): not smoking, regulating second-hand smoke in public places (which has improved considerably, with broad social consensus), better control of toxic industrial emissions and better regulation of crop and livestock farming.

Internal contamination affects a person differently according to their gender, age, social class and other parameters.

We have to always prevent contamination, as a habit almost or entirely unconsciously. But it is true that there are life stages that are more sensitive to toxic effects. For example, before becoming pregnant, when a couple is trying to have a child, they should be more careful, and during childhood, puberty and menopause as well… Even though there are more susceptible ages, we should be thinking preventatively at all ages. Each person should get information from quality sources, talk about it with their inner circle and find their own way to improve. Each of us has to do things our own way. This includes political and personal responses.

Sometimes public policies work (such as food regulations or the success of lowering the amount of lead in our bodies). What advances have been made (public policies, private policies, etc.) to lower internal contamination? And what measures do you think should be urgently implemented?

One good example, even though it’s imperfect, is REACH, the European Union’s programme to register chemical products. It is known worldwide and reminds us that we all live in a village called Earth, because the programme also forces companies from Asia and America that want to sell the wares in Europe to comply as well. REACH entered into force in June 2007 to register, evaluate, authorise and restrict the use of certain chemical substances. It was adopted with the goal of boosting the protection of human health and the environment against the risks which chemical products can pose, while also enhancing the competitiveness of the EU’s chemical industry. It doesn’t work well enough, since one-third or more of the cases don’t meet the standards. Substances are registered – which later appear in our dishes, furniture or toys – without providing information that guarantees that they are not teratogens (which cause congenital malformations), carcinogens or endocrine disruptors. We have to vote for politicians who will work to ensure that REACH works much better.

There are many effective policies in force in Spain, and I’m afraid that we don’t value them enough. As a simple example, many town halls have banned glyphosate. There are towns and autonomous communities that work very actively to prevent food, water and air pollution.

Regarding organic products, are we sure these products do not contain toxins? Do you recommend that people eat a 100% organic diet?

Generally speaking, there is much less pollution in organically-farmed foods, but there can be some. The European Food Safety Authority, EFSA, headquartered in Parma, has also documented this with valid data. Those in charge of organic certification do a commendable job, in my opinion. They tend to look at whether or not certain substances are over the legally stipulated limits, but seldom do they make comparative analyses with industrially-farmed products. They have neither the legal mandate nor the means to do so. Only universities seem to be doing a handful of analyses of contaminants in organic, intermediate and industrial foods, while public administrations tend not to be involved in this. That has to change.

Is making changes in our diet and habits (lowering the use of plastics, food, etc.) more important because of the effects it can have on our bodies (lowering toxins) or because they entail a paradigm shift, a change in society’s habits and in the conception of the world which will affect future generations even more?

I get the sense that on a key issue like plastic we are at a major turning point. Awareness, behaviours and some policies (such as on the Balearic Islands) are changing for the better. But more regulation, more policies, are needed, without ignoring cultural factors, like traditional local markets, which are a wonderful place to buy higher-quality foods, use less plastic and exchange practical knowledge.

What role does the current economic system, profit-driven capitalism, play in the increase in toxins? Does lowering the toxins in our bodies necessarily entail a new, degrowth-oriented economic model?

Different capitalist systems coexist in the world; it’s not a homogeneous, unified system. Plus, when we answer these questions publicly and privately, we often make the mistake of thinking that everyone should act the same and that we can promote a single solution for everyone. And that’s simply not true: a range of opinions and answers is inevitable, and it’s a good thing. Each person has to ask their own questions about contamination in their own way, including analyses and policy options (local, regional and global). The colossal injustices, fears and frustrations today should not prompt only emotional, populist and ideologically superficial answers but also, and more importantly, brave, innovative political responses with real effects not burdened with 20th-century dogmas.

Health is an important, recurring concern among citizens, as shown in surveys. Does the media’s agenda treat health-related issues well enough?

The most toxic and unproductive financial powers (which obviously does not include all of them) have neither morals nor compassion: they are only concerned with their own privileges, not health or the real economy. The media that does not actively back citizens (such as, by paying) and the media agendas dictated by toxic powers always try to distract our attention away from what truly counts (public health; economic, social and environmental influences on health and illness) and towards what interests them (public financing of private medicine, increasing private spending on diagnosis and treatment, wrapping up healthcare companies that do not conduct research in prestigious university labels, blaming individuals for their ailments, etc.). But health-related journalism has improved drastically since I studied at the UAB because we gained freedom and now have a much higher level of democracy, and because many of us continue to work to raise it. And at the UAB we have amazing human and academic capital working to strengthen the structures and processes that influence health the most positively: the economy, education, food, animal health and public health, the environment, labour, communication, culture and medicine. I am very pleased to belong to this university community, to work hard but happily, to demand more of ourselves and to be appreciated by students and society. Thank you so much for allowing me to give this lecture, for interviewing me and, to the readers, for reading me.