"Africa's youth should be seen as a global opportunity"

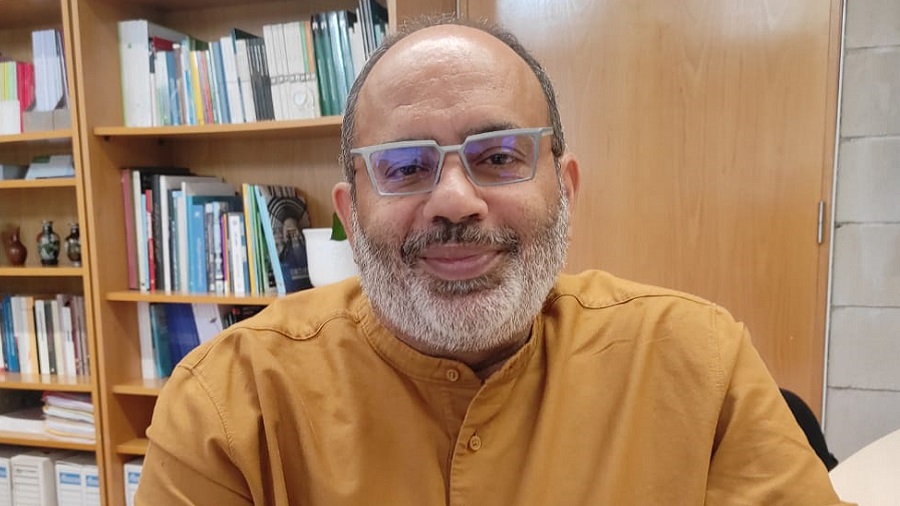

Sociologist and economist Carlos Lopes (Guinea-Bissau, 1960), Honorary Professor at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and African Union High Representative for Partnerships with Europe, offered a conference entitled "Africa in Transit: diversity, dilemmas, futures" on 17 March at the UAB Faculty of Translation and Interpreting. The event was organised by the faculty and the José Saramago Chair.

You explain in your blog that, disillusioned by the political deviation of your country, you decided to pursue a career in the United Nations. Are you satisfied with the result of this "vital leap"?

After 28 years of experience in the United Nations, I believe I am. It helped me understand the limits of a very idealogical vision of pan-Africanism and made me try to contribute to the evolution of this concept towards a structural transformation of African economies. In its origin, pan-Africanism was a concept more related to the dignity of the black population and the development of its diaspora rather than to the continent; it was directly related to freeing ourselves from colonialism. Currently, it implies debates on the creation of a free trade zone and on other aspects, and I was able to contribute to these debates by working in the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

Should countries yield more power to large international organisations such as the Africa Union or the United Nations to advance towards a more efficient global governance?

Without more yielding of power, Africa would not be able to participate in large international negotiations. This is very clear when it comes to trade: if Africa speaks using only one voice, it has a high intervention capacity. During the pandemic, African countries wanted to have a special intellectual property regime for vaccines and they managed to change the legislation of the World Trade Organisation expressing themselves with only one voice; that was a demonstration of power. Another example was the grain negotiations due to the war in Ukraine: there was a need for grains and fertilisers to circulate freely, and Africans put on a lot of pressure to reach an agreement with the participation of the two parts and the mediation of Turkey.

There is talk about the enormous influence China has on the continent. Is Africa in risk of becoming, as in colonial times, a land disputed over by world powers?

There will be disputes because we are entering a period of geopolitical tension, but I do not believe there is a possibility of China controlling the continent. What China is aiming for is to enlarge its market so that it can trade more, as well as have political influence in a scenario of international tension. However, when one takes a closer look at the presence of China in Afica, the conclusion is that there is not much to worry about. For example, China's investment in Africa is equivalent to its investment in Pakistan. For a region as large and with the population of Africa, a yearly investment of 10 billion dollars is not that much, but it is enough to make China the most important supplier of government debt. And the same can be said for commerce. Or, if we talk about infastructures, China is very visible, while the investments of other countries are not as easily seen. If you invest in a port, an airport or railway line, it is much more visible than if you invest in mining.

The image of Africa in Western countries is closely associated with serious problems with peace, nutrition and health. What is the part of today's Africa that we are not seeing?

Everything you mention is true, but it is taken out of context. For example, there are more homocides in the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro than in all of the African Great Lakes region. There are more victims of conflict in India—including the Kashmir conflict and the Naxalite-Maoist insurgency—than in the Horn of Africa. But is not how it is peceived, because the conflicts in Africa are highly exposed. The United Nations Security Council's agenda always includes Africa, 60% of its debates focus on the continent and not on what happens in Myanmar or North Korea because there are permament members of the council who do not allow these countries to be put on the agenda.

The other part of the explanation is that Africa follows demographic, climate and technological dynamics that in the long run will place the continent at the centre of large global decisions. Africa's population is young at a time in which public healthcare systems cannot absorb the changes in the populational pyramid of richer countries. From a technological perspective, consuming technological products is appealing to young people, so Africa will be an essential market for the future. And from the point of view of the climate, the energy transition and new means of transport will need the resources found in large quantities in Africa. The continent will become a sort of energy and mineral megapower in the transition we need to make to solve the climate crisis.

When we talk about demographic growth, are the governments in Africa taking any type of management measures?

Demographs point to a demographic transition when a peak in fertility is reached and the population pyramid begins to change. This is what is happening now in China and what happened years ago in Europe. Except for the United States of America, which is a singular case due to its large amounts of immigration, the OECD countries are undergoing a demographic transition that is leading them towards an ageing population. Thus, Africa's youth should not be seen as a continental problem, but as a global opportunity. The countries faced with a shortage of skilled labour and that need young workers, and the demographics of Africa must be observed within this global context.

The UAB Publishing Services recently published the book África: cambio climático y resiliencia. Retos y oportunidades ante el calentamiento global by Johari Gautier. Among other things, it speaks about the project to create the Great Green Wall to stop desertification in the Sahel. Has there been any progress?

From a scientific point of view, this is the demonstration that it is possible to reforest an area that was believed to be lost as the Sahara desert advances towards the south. And it is also the way to mobilise the support needed to treat Sahel differently. Not only does the project include planting trees, it is also a project to integrate the populations in that region. In all countries in which the farming population is large, there are conflicts because the farmers work with an economy they understand in terms of livestock, and the results are very difficult to apply in a more formal and complex economy, based on value chain criteria and so on. They do not feel integrated and use their knowledge of the region and their skills in other things, such as turning to jihadism. This type of economic structure is what must be changed.

What role do African universities play in the social and economic development of the continent?

I work at the University of Cape Town, which is among the top 150 most advanced universities in the world and in some areas such as Medicine, it ranks among the top 60. According to all the rankings, we are the top university in Africa, and it is a sort of pan-African centre of knowledge. But there are very large differences among universities and some of them suffer greatly. In the 1980s and 1990s, there was a huge drop in university funding, and this had a great impact on the quality of the programmes, and it was very difficult to return to that level of quality. And now, there is also the need to include new digital technology and promote blended and distance learning.

The UAB, with Sustainable Development Goals

Decent work and economic growth

Peace, justice and strong institutions

No poverty

No povertySustainable cities and communities

Partnerships for the goals

Climate action