The disappearance of mastodons still threatens the native forests of South America

A study with the involvement of the UAB, IPHES-CERCA and URV, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, provides for the first time direct fossil evidence of frugivory in South American mastodons and shows the lasting ecological impact of their extinction.

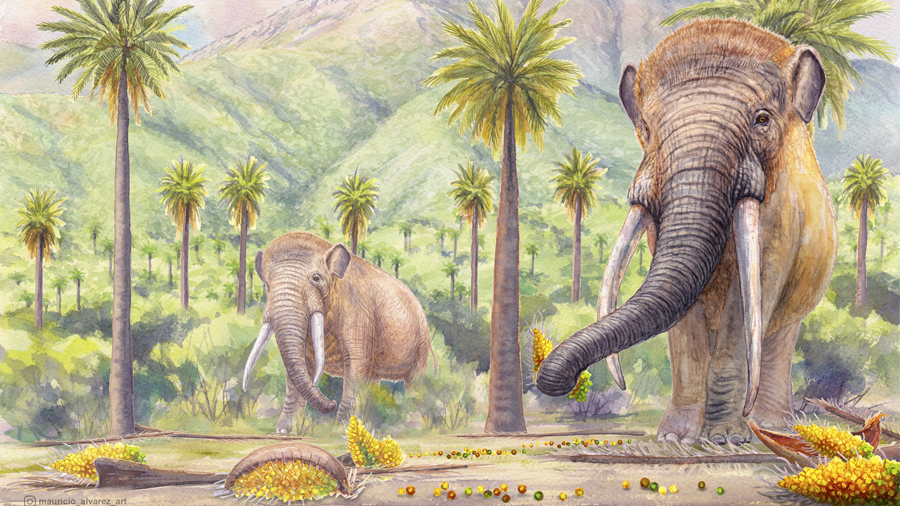

Ten thousand years ago, mastodons vanished from South America. With them, an ecologically vital function also disappeared: the dispersal of seeds from large-fruited plants. A new study led by the University of O’Higgins, Chile, with key contributions from IPHES-CERCA, demonstrates for the first time—based on direct fossil evidence—that these extinct elephant relatives regularly consumed fruit and were essential allies of many tree species. Their loss was not only zoological; it was also botanical, ecological, and evolutionary. Some plant species that relied on mastodons for seed dispersal are now critically endangered.

Published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, the research presents the first solid evidence of frugivory in Notiomastodon platensis, a South American Pleistocene mastodon. The findings are based on a multiproxy analysis of 96 fossil teeth collected over a span of more than 1,500 kilometers, from Los Vilos to Chiloé Island in southern Chile. Nearly half of the specimens come from the emblematic site of Lake Tagua Tagua, an ancient lake basin rich in Pleistocene fauna, located in the present-day O’Higgins Region.

The study was led by Erwin González-Guarda, researcher at the University of O’Higgins and associate at IPHES-CERCA, alongside an international team that includes IPHES-CERCA researchers Florent Rivals, a paleodiet specialist; Carlos Tornero and Iván Ramírez-Pedraza, experts in stable isotopes and paleoenvironmental reconstruction; and Alia Petermann-Pichincura. The study was carried out in collaboration with the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV) and the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), where Carlos Tornero is professor in the Department of Prehistory.

An ecological hypothesis finally proven

In 1982, biologist Daniel Janzen and paleontologist Paul Martin proposed a revolutionary idea: many tropical plants developed large, sweet, and colorful fruits to attract large animals—such as mastodons, native horses, or giant ground sloths—that would serve as seed dispersers. Known as the “neotropical anachronisms hypothesis,” this theory remained unconfirmed for over forty years. Now, the study led by González-Guarda provides direct fossil evidence that validates it.

To understand the lifestyle of this mastodon, the team employed various techniques: isotopic analysis, microscopic dental wear studies, and fossil calculus analysis.

“We found starch residues and plant tissues typical of fleshy fruits, such as those of the Chilean palm (Jubaea chilensis),” explains Florent Rivals, ICREA research professor at IPHES-CERCA and an expert in paleodiet. “This directly confirms that these animals frequently consumed fruit and played a role in forest regeneration.”

The forgotten role of large seed dispersers

“Through stable isotope analysis, we were able to reconstruct the animals’ environment and diet with great precision,” notes Iván Ramírez-Pedraza. The data point to a forested ecosystem rich in fruit resources, where mastodons traveled long distances and dispersed seeds along the way. That ecological function remains unreplaced.

“Dental chemistry gives us a direct window into the past,” says Carlos Tornero. “By combining different lines of evidence, we’ve been able to robustly confirm their frugivory and the key role they played in these ecosystems.”

A future threatened by an incomplete past

The extinction of mastodons broke a co-evolutionary alliance that had lasted for millennia. The researchers applied a machine learning model to compare the current conservation status of megafauna-dependent plants across different South American regions. The results are alarming: in central Chile, 40% of these species are now threatened—a rate four times higher than in tropical regions where animals such as tapirs or monkeys still act as alternative seed dispersers.

“Where that ecological relationship between plants and animals has been entirely severed, the consequences remain visible even thousands of years later,” says study co-author Andrea P. Loayza.

Species like the gomortega (Gomortega keule), the Chilean palm, and the monkey puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana) now survive in small, fragmented populations with low genetic diversity. They are living remnants of an extinct interaction.

Paleontology as a key to conservation

Beyond its fossil discoveries, the study sends a clear message: understanding the past is essential to addressing today’s ecological crises. “Paleontology isn’t just about telling old stories,” concludes Florent Rivals. “It helps us recognize what we’ve lost—and what we still have a chance to save.”

Reference: González-Guarda, E. et al. Robust fossil evidence for proboscidean frugivory and its lasting impact on South American ecosystems. Nature, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02713-8