“The effects of PISA depend on the political use it is given”

27/02/2017

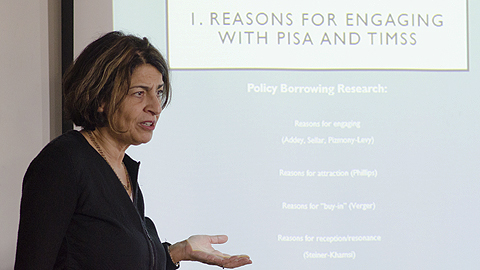

Professor of Comparative and International Education and of International and Transcultural Studies at Teachers College,Columbia University of New York, Gita Steiner-Khamsi spoke on her research and international student assessment programmes such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS).

- Why are international assessments such as PISA and TIMSS so important in current educational discussions?

- I think we have to put this in a bigger context in how the role of the state has changed in the past 20 years in Europe and more recently in other countries. The state should increasingly assume the role of a regulator of quality and standards in education, and not just the provider. This of course is the result of "market thinking" in education. Some colleagues call it "neo-liberal reforms", others, such as Antoni Verger here at the UAB call it the "market model". This type of model opens up at the input side, with the idea that everyone should be providing education, not only the government, but the state is the one which should make sure that the quality is good. This is at all levels of the education system: in higher education, with all the accreditation policies, to open up to private universities, private providers. And of course the easiest way to regulate and enforce or monitor standards is to test students. Because at the end of the day, it is the student who should have learned something.

Therefore, one reason has to do with the changing role of the state as a regulator in this new neo-liberal quasi-market model of how reform is done. The other reason is something we call "governance by number", in which there is increasing pressure on public education to show that the money spent is for good purposes, and the education system must show results and outcomes. A third reason is a growing middle class with educated parents who want to make choices and participate in the process.

There are many reasons, but it is interesting to see education become a public and political issue, not just something discussed among experts. So we are actually happy about education becoming an issue for public debate and discussion.

- How are they influencing the current educative policy at both national and supranational levels?

- I would turn the question around and not ask how does OECD, or PISA, etc. influence them, but how do national or regional authorities use them, and for what purposes. Therefore, I would look at the question from an active construction. It is very interesting to see a growing group of scholars emerging, with colleagues such as Sam Seller, Camila Addey, Bob Lingard, Antoni Verger or Oren Pizmony-Levy, my colleague at Columbia University, who are looking at "reasons for engagement with PISA". This engagement varies in different countries and for different reasons. In some countries, the poor results in PISA have been used to generate reform pressure. This happened in Germany with the "PISA shock" and it happened in other countries where they were very happy that the school system did not yield positive results. In Denmark, for example, an OECD study from 2004 was very influential on the nation's education system. Studies we conducted with colleagues at the Danish School of Education of Aarhus University (DPU) show that the government used the study to generate reform pressure which lasted 10 years and ended in the reform of 2014. Therefore, PISA results do not have to be good to have an impact. In fact, they have a larger effect if they show poor results.

And other countries use this technique. National policy actors use it to generate reform pressure and coalitions, to bring political parties on board to support reforms, which are very often fundamental reforms. Others use it to mobilise resources, to generate public funds for education and show there is a need to invest more. Some reasons are very banal, such as for "item construction", in which they learn from PISA how formative student evaluations are done.

The reasons may be different even within a country. And in some countries, neither PISA nor TIMSS are not important at all. In the US, for example, they is barely noticed. And there are a variety of reasons for that, too. One is that education policies are not done at national or federal level; they are done at state level and schools play a huge role in implementing the policies. Therefore, a move towards a “school-based management” or "side-based management" has a low interest in this type of comparison. And the US in general tends to compare states within the country, rather than looking at Europe; except for the UK perhaps.

- What are the positive and negative effects of these assessment programs on education and educational systems?

- A truly negative effect is that student tests are the easiest way to measure quality and the performance of the education system. It is uncontested. Many education systems, such as Switzerland where I lived for a period before moving to the US, and Portugal, try to have more sophisticated surveys, and self-evaluation tools. In the end, the quickest and most powerful way to make an assessment is a student test. This is negative, because it does not accurately reflect the quality of education. There is more to learning than only literacy, science and the core subjects. As a result, some school systems emphasise these subjects more and neglect the ones which are not tested.

Also, the popularity of PISA and public and political interest tends to generate more standardised tests in schools. This is a problem, since there is pressure on teachers within this accountability reform model, and they are encouraged to teach for the tests, which takes time away from meaningful learning. These are some of the negative effects. In some countries, in the UK and the US, families have come together and voiced their opinion against these types of tests.

The positive effect is that they are a policy tool. It depends on what politicians and policy makers do with them. Some use them to generate reform pressure, some to mobilise funds and receive more support for education. In this sense, it can be positive or negative, depending on the use it is given in different national contexts.

- You have studied how different media outlets treat these programmes.

- Yes, I worked on this issue with two students at Columbia University, Margaret Appleton and Shezleen Vellani, and we looked at three different media outlets, The Economist, the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal. We wanted to see how they discussed public education and school reform, but also specifically how they talked about PISA and TIMSS, because they are the two big international assessment programmes.

It was interesting to see how education had become an issue, with PISA being more talked about than TIMSS. And there are different explanations for that. The weekly magazine The Economist in particular is keen on discussing education issues. Interestingly, the magazine belongs to Pearson, which is a large multinational testing company, and has become very big in the global education industry. And it was surprising to see how three newsletters associated with the business community, not with parents or policy makers, are interested in education. And we tried to understand not only why they are looking at these tests, but also how they talk about education.

One of the things we discovered through quantitative and qualitative analyses was that accountability was important; not so much the amount the government was spending, but that they made sure the money was spent the right way. We were trying to understand the business logic of why they were so interested in education.

- What is the global education industry and who forms part of it?

- Several conditions need to be met to be able to talk about a global education industry. It needs to be transnational, a business in several countries. and it must be focused on education, and it must be for-profit. There are many NGOs which do not fit in such a narrow definition of a global education industry. For instance, Pearson is an example of the global education industry. There are the Omega schools, game schools, some of these operate in 10, 20 countries, some only in OECD countries, others in Africa, in India, etc. They are always for-profit, always at the transnational level, and always focused on education.