Genetic study revives debate on origin and expansion of Indo-European languages

02/03/2015

Migration processes allow scientists to determine whether or not to give support to the linguistic and archaeological theories on the diffusion of languages and cultural material throughout history. In the case of Europe, one of the still unsolved enigmas is the origin and diversification of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language, considered the source of the majority of languages spoken today in Europe, Asia and America.

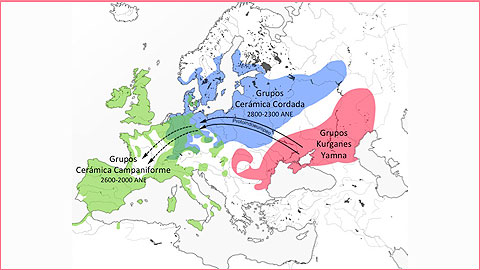

In contrast to the Anatolian hypothesis, which defends that the diversification of PIE occurred some 8,500 years ago, when the first farmers from the Near East (currently Turkey) brought it to Europe, there is the Kurgan hypothesis, which proposes that the language was spread by nomadic herders of the steppes found to the north of the Black and Caspian Sea, and that their language spread throughout Europe after the invention of wheeled vehicles, from 6,000 to 5,000 years ago.

Now, an international team of researchers, with the participation of UAB Prehistory professor Roberto Risch, has conducted a genetic study which backs this second hypothesis; they identified a massive migration of herders from the Yamna culture of the North Pontic steppe (Russia, Ukraine and Moldavia) towards Europe which would have favoured the expansion of at least of few of these Indo-European languages throughout the continent.

At the same time, data indicates that, contrary to the dominant view in recent decades, today's European populations do not descend only from the first hunters-gatherers and from the people arriving during the Neolithic expansion of the Near East.

The research demonstrates that Eastern and Western European populations followed different paths 8,000 to 5,000 years ago, and that they did not come into contact with each other until 4,500 years ago, when the populations of Eastern Europe associated with the Corded Ware culture settled into a large part of Central Europe. These populations have been proved to be genetically very similar to individuals buried in the Yamna kurgans found to the north of the Black Sea (currently Russia and Ukraine), and very different to the Palaeolithic and Neolithic populations of Western Europe.

Researchers observed that the lineage of Corded Ware culture individuals in Germany matched in more than 75% that of the Yamna populations. This would imply the occurrence of a massive migration of men and women from herder societies of the North Pontic steppe towards Central Europe. This genetic link exists in Central European samples dating back 3,000 years ago the furthest DNA samples go back until now), and can still be found among today's European population. While in Northern and Central Europe this link represents around 50% of the current gene pool, the percentage in the Iberian Peninsula is of approximately 25%.

“Although ancient DNA tests cannot inform about the language spoken by the prehistoric humans analysed, the magnitude of the migratory movement would also have implied a language change. If what the genetic data states is true, and these populations live on, they must have contributed to the formation of the Indo-European languages spoken today in Europe," explains Roberto Risch.

The research also determines that before the migration of the Yamna herders, the first European farmers in Hungary, Germany and the Iberian Peninsula were genetically very homogeneous, and that the more primitive hunter-gatherer societies living in Europe did not immediately disappear; they reappeared genetically some 5,000 to 6,000 years ago. During that same period, the Yamna herders descended from the hunter-gatherer societies of Eastern Europe and from an ancestral population of the Near East.

The work, led by geneticists Wolfgang Haak from the University of Adelaide, Australia; Kurt Alt from the University of Mainz, Germany; and David Reich and Losif Lazaridis from the Harvard Medical School in Boston, represents the largest genetic study conducted to date.

Researchers studied the ancient genome of 69 Eurasian individuals dating back 8,000 to 3,000 years ago, and used new techniques on the key positions of nuclear DNA, which allowed them to study twice as many ancient nuclear DNA samples from Europe and Asia than those in previous studies and conduct precise estimations on the proportion of genetic mixture in individuals.

By adding to this database the already published results of another 25 individuals it was possible to create a statistical model of the genetic proximity of 94 prehistoric women and men.

Future Research: the Iberian Peninsula

The study does not reveal the precise origin of PIE, nor does it clarify the impact Kurgan migrations had on different parts of Europe. In the case of the Iberian Peninsula, there is a special need to determine the genetic filiation of populations from the Copper and Bronze Ages (5,000 - 3,000 years ago).

The Mediterranean Social Archaeoecological Research Group (ASOME) of the UAB Department of Prehistory is working closely with this international work group in this direction.

“In particular, what must be determined is the location in Europe's palaeogenetic map of one of the most unique prehistorical societies, the Argar. This is the first state-type society with specialised metallurgical know-how in Western Europe and appeared some 4,200 years ago in the south-east of the Iberian peninsula," professor Risch points out.

Historical Implications of Genetic Results in Western Europe

In the elaboration of the study, whose first results are now published, the work carried out in the past decades by the researchers of the UAB ASOME group played an important role in the information it offers on the creation of the first proto-state and state-type societies in Western Europe.

In recent decades, the idea has existed that there was an increase in social inequalities between the end of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age (from 5,500 to 4,000 years ago), a process which would have been gradual and, to a large extent, peaceful. Some specialists, including Roberto Risch, nevertheless have pointed out that during that period decisive economic and political changes were taking place in the Caucus and the North Pontic Steppes. In addition to certain technological innovations, such as the invention of the wheel and the production of more efficient bronze tools and weapons, there was also a change in burial rites. People were buried in individual tombs and differences existed between the burial rituals of men and women. The richest grave goods, made up of tools, specialised weapons and metal ornaments, were concentrated among a reduced group of male tombs. The link between males, power and metallurgy existed even in regions in which there were no mineral resources, and burial rituals were marked by the placement of crucibles and anvils next to the corpse. This burial ritual, which aimed to mark sexual and economic differences based on the control of technology and possession of weapons, is precisely what is introduced into Central and Western Europe from the Caucus and the Russian steppes 5,000 years ago.

“The data now published suggest that the changes at that moment did not occur only through the transmission of concepts and knowledge, but also thanks to the expansion of patriarchal kinship groups, weapons and power structures which were until then unknown to the Neolithic communities of Western Europe," Roberto Risch concludes.

Article: "Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe." Nature.