Evaluation of Fukushima effects on oceans

01/07/2016

According to the review, the levels of radiation are decreasing rapidly except in the harbour area close to the nuclear plant itself where ongoing releases remain a concern. Among the conclusions, scientists highlight that the maximum levels of radiation, which do not pose a risk to life, will be arriving this year to the North American coasts and that the risk of radiation to people is very low. Researchers express their concern at the lack of ongoing support to continue the radiation assessment, vital to understanding how the risks are changing.

The review, presented by researchers from the working group of the Scientific Committee in Oceanic Research (SCOR), is also being published as an article in the Annual Review of Marine Science. The main points made by the report are:

The accident

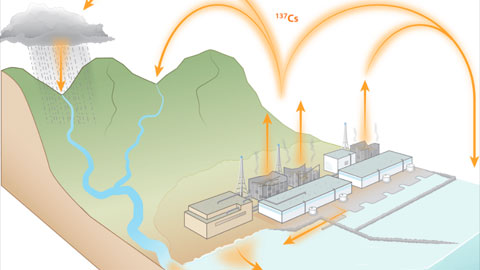

The Tohoku earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011 led to the loss of power and overheating at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plants (FDNPP), causing extensive releases of radioactive gases, volatiles and liquids, in particularly to the coastal ocean. The radioactive fall-out on land is well-documented, but the distribution of radioactivity in the seas and onto the wider oceans is much more difficult to quantify, due to variability in the ocean currents and greater difficulty in sampling.

Initial release of radioactive material

Although the FDNPP accident was one of the largest nuclear accidents and unprecedented for the ocean, the amount of 137Cs released was around 1/50th of that released by the fall out of nuclear weapons and 1/5th that released at Chernobyl. It is similar in magnitude to the intentional discharges of 137Cs from the nuclear fuel reprocessing plant Sellafield.

Initial fallout

The main release of radioactive material was the initial venting to the atmosphere. Models suggest that around 80% of the fallout fell on the ocean, the majority close to the FDNPP. There was some runoff from the land, peaking around 6 April 2011. There is a range of estimates of the total amount of 137Cs release into the ocean, with estimates clustering around 15-25 PBq (PetaBecquerel, which is 1015 Becquerel. One Becquerel is one nuclear decay per second). Other radioisotopes were also released, but the focus has been on radioactive forms of Cs given their longer half-lives for radioactive decay (134Cs = 2 yrs; 137Cs = 30 yrs) and high abundance in the FDNPP source.

Distribution in water

Cs is very soluble, so it was rapidly dispersed in the ocean. Prevailing sea currents meant that some areas received more fall-out than others due to ocean mixing processes. At its peak in 2011, the 137Cs signal right at the FDNPP was tens of millions of times higher than prior to the accident. Over time, and with distance from Japan, levels decrease significantly. By 2014 the 137Cs signal 2000km North of Hawaii was equivalent to around six times that remaining from fallout from atmospheric nuclear tests from the 1960’s, and about 2-3 times higher than prior fallout levels along the west coast of N. America. Most of the fallout is concentrated in the top few hundred metres of the sea. It is likely that maximum radiation levels will be attained off the North American coast in the 2015-16 period, before declining to 1-2 Bq per cubic metre (around the level associated with background nuclear weapon testing) by 2020. Sea-floor sediments contain less than 1% of the 137Cs released by the FDNPP, although the sea-floor contamination is still high close to the FDNPP. The redistribution of sediments by bottom-feeding organisms (more common near the coast) and storms is complex.

Uptake by marine life

In 2011, around half the fish samples in coastal waters off Fukushima had radiocesium levels above the Japanese 100Bq/kg limit, but by 2015 this had dropped to less than 1% above the limit. High levels are still found in fish around the FDNPP port. High levels of 131I were measured in fish in April 2011, but as this has a short radioactive half-life, it is now below detection levels. Generally, with the exception of species close to the FDNPP, there seem to be little long-term measurable effects on marine life.

Risk to Humans

The radiation risk to human life is comparatively modest in comparison to the 15,000 lives were lost as a result to the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. So far, there have been no direct radiation deaths. The most exposed FDNPP evacuees received a total dose of 70 mSv, which (if they are representative of the general population) would increase their lifetime fatal cancer risk from 24% to 24.4%. However, there are still over 100,000 evacuees from the Fukushima area, and many industries such as fishing and tourism have been badly hit.

Reference article

Buesseler, K.O., Dai, M., Aoyama, M., Benitez©\Nelson, C., Charmasson, S., Higley, K., Maderich, V., Masque, P., Oughton, D. and Smith, J.N. 2017. "Fukushima Daiichi–derived radionuclides in the ocean: transport, fate, and impacts." Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 9:In press. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060733

http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-marine-010816-060733