Children under three learn new words even when speakers wear masks

A study from the UAB show that, from the age of two, children are able to create associations between words and unfamiliar objects, after a brief audiovisual interaction and suggests that infants’ optimal attention strategy for acquiring new vocabulary involves following the speaker's gaze and focusing on the object, but does not depend on focusing on mouth or eye movements.

A research team from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and the University of Grenoble Alpes - Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) has shown that from the age of two, children can learn new words even when the person talking to them has their mouth or eyes covered. According to this study, vocabulary learning at this age is associated with following the speaker's gaze and focusing on the object shown to them when the new word is pronounced, but does not depend on selective attention to the speaker's mouth or eyes.

These results offer reassurance about the use of facemasks and their potential impact on the language development of young children, a concern raised by families and childcare professionals during the COVID pandemic.

The study, published in the journal Developmental Psychology, is the first to show that, from the age of two, children are able to learn new vocabulary, i.e., to create associations between words and unfamiliar objects, after a brief audiovisual interaction. At the same time, it underlines the importance of social reference - looking at the speaker for reinforcement of their response - and attentional control in learning new words.

Exploring how children's attention affects vocabulary learning

Both gaze following skills and selective attention to a speaker’s mouth have been associated with the dramatic improvement in word acquisition that occurs during the second year—a phenomenon known as the vocabulary boost. This has led some experts to propose that both attention strategies may play a key role in the lexical development of infants. However, until now, no cause-effect relationship has been found to validate this hypothesis.

"Previous studies suggested that looking at the speaker's mouth facilitates children’s speech processing and, specifically, the understanding and memorisation of new words, thanks to the visual cues provided by mouth movements. If so, wearing a mask should hinder the learning of new words", explains Joan Birulés, researcher at the Department of Basic, Developmental and Educational Psychology at the UAB and first author of the study.

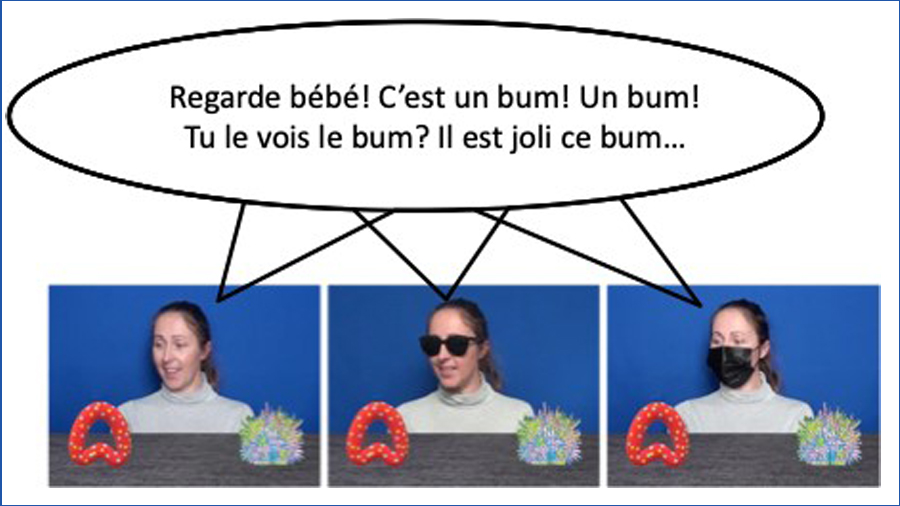

To investigate this further, the research team recorded the gaze of French children aged between 17 and 42 months while they participated in a word learning task in one of three situations: with the speaker's face completely visible, with their eyes covered with dark glasses, or with their mouth covered by a surgical mask. In the task, infants were shown a screen with a speaker and an object on both sides. The speaker uttered a monosyllabic word six times and, simultaneously, on two occasions shifted the gaze to the object associated with the word.

Results showed that children learned new words starting at 24 months and, surprisingly, that this learning was not affected by the glasses or mask. Better word learning was correlated with gaze-following behaviour—moving the gaze towards the object and alternating between the speaker's face and the object—across all ages and conditions. While masking the eyes or mouth modified attention patterns and made infants focus more on the uncovered facial regions, this manipulation did not affect their ability to form new associations between the new word label and the object.

“The results indicate that children's optimal attention strategy is based on social understanding and visual exploration of the object, and that audiovisual information from the speaker's mouth is not an essential mechanism for rapidly establishing new associations between words and their meaning, at least in typically developing children and in learning or fast mapping contexts”, the researcher adds.

In the bare-face situation, moreover, children preferred to look at the speaker's eyes rather than at the mouth, contrary to previous studies in children exploring the interlocutor's face. This leads the research team to consider that children aged 1.5-3 years are already able to control visual attention in a flexible way, adjusting selective attention between the interlocutor’s eyes and mouth, depending on the task requirements.

Strategy to enhance word learning

Based on the results of the study, the researchers suggest that an effective strategy to enhance word learning in infancy would be to encourage deeper exploration of the object in question, along with rapid visual shifts between the object and the speaker's face.

However, they do not rule out that attention to the speaker's mouth could be beneficial in more complex speech-processing situations, such as in children with hearing impairments, language disorders, or autism spectrum disorders. “In such cases, visual cues from the mouth could become essential, a question we are currently exploring in collaboration with health centres in Grenoble”, says Joan Birulés.

Article: Birulés, J., Pascalis, O., Méary, D., Fort, M. Covering the eyes or mouth of a speaker does not prevent word learning in typically developing infants. Developmental Psychology, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0002016