New research explains the secret of longetivity of the Sicilian dwarf elephant

The paleohistological study of its bones, published in Scientific Reports by ICP researchers, provides evidence that this species had a minimum lifespan of 68 years and attained maturity at the age of 15. This dwarf elephant is an iconic example of how faunas evolve on islands.

Islands are exceptional natural labs to study evolution. Their geographic isolation hindering the migration of species from mainland, the absence of predators (which usually require large areas of land to hunt), or the low resource availability of island ecosystems, drive some common evolutionary patterns in the inhabiting faunas. One of these phenomena is dwarfism or gigantism; animal species on islands have the tendency to become either giants or dwarfs in comparison to their mainland relatives. This trend is especially pervasive among mammals and dinosaurs.

By the middle of the 19th century, Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace were already interested in this phenomenon after their expeditions to several islands around the world, and from where they obtained evidences that would lead them to formulate the Theory of Evolution. In 1973, based on Foster’s earlier work, the evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen formulated the “island rule”, stating that insular animal species follow an evolutionary pattern when it comes to their body sizes.

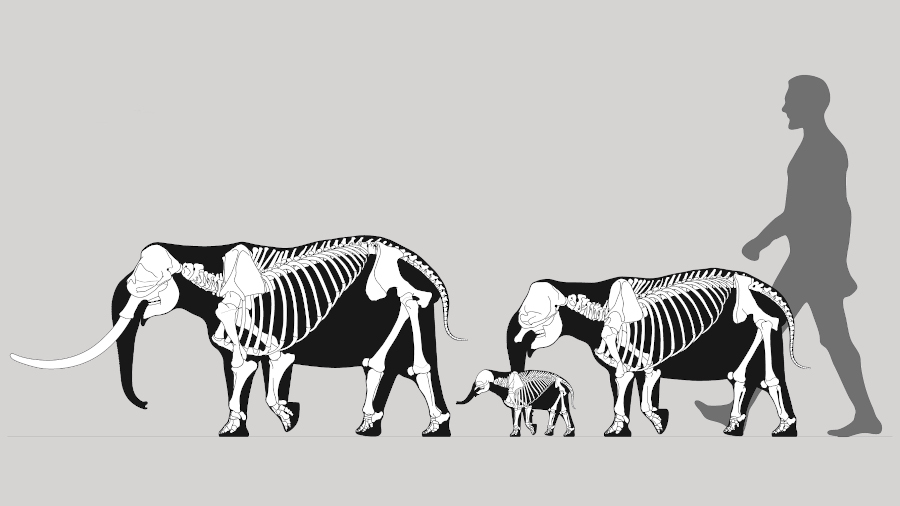

One of the iconic species of this island rule is the Sicilian dwarf elephant, Palaeoloxodon falconeri. Compared to extant elephant species it is extremely small, about one metre tall and an estimated weight of 250 kilos. It lived on the island of Sicily during the Pleistocene, between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago, and is known for the fossil remains that have been found in different sites on the island. P. falconeri is a descendant of the much larger continental species P. antiquus, up to five metres high at the withers and 5 tonnes of estimated body mass.

Now, an article published in Scientific Reports led by researchers from the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP), a research centre ascribed to the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), in collaboration with several international research institutions describes the ‘life history’ of this species. This term refers to the characteristics of the different events that take place during the life cycle of an animal, such as its growth rate, age of sexual maturity or longevity. The study concludes that the Sicilian dwarf elephant grew very slowly, reached sexual maturity at the age of 15 years and had a long lifespan of at least 68 years.

“Traditionally, this species had been considered to have a rapid development, reaching sexual maturity early and having a short life”, explains Meike Köhler, ICP researcher and ICREA professor leading the research. “Our work reveals that the life history of this elephant was much slower”, she concludes.

The research team analysed the palaeohistology – the internal structure of fossils – of this species’ molars and tusks. “The different events along the life cycle of an animal are recorded in its bones, in a similar way that growth patterns of a tree are recorded in a section of its trunk”, explains Köhler. Fossils are cut into slices of approximately 0.1 mm thick and the Lines of Arrested Growth (or LAGs) are analysed under the microscope to identifying the growth and latency periods of the animal.

In general, small continental species tend to have faster life histories: they grow fast, reproduce early, and die young. “But in the islands exactly the opposite happens”, explains co-author of the research Salvador Moyà, ICP researcher and ICREA professor. Unlike mainland, changes in body sizes of insular species are not associated with a faster life history. “We have found that the Sicilian dwarf elephant had a much slower life history than its sister taxon P. antiquus and the huge African savanna elephant”, says Moyà. “The slow pace of this animal is the key to its longevity. Maybe we humans could learn something from them!”, jokes Moyà.

In addition to Moyà and Köhler, the research team is made up of Carmen Nacarino and Josep Fortuny (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont), Victoria Herridge (Earth Sciences Natural History Museum, London), Blanca Moncunill (Università degli Studi Roma Tre), Antonietta Rosso and Rossana Sanfilippo (Università di Catania), and Maria Ritta Palombo (Sapienza University of Rome).

Original article

Köhler, M., Herridge, V., Nacarino-Meneses, C., Fortuny, J., Moncunill-Solé, B., Rosso, A., Sanfilippo, R., Palombo, M. R., Moyà-Solà, S. Palaeohistology reveals a slow pace of life for the dwarfed Sicilian elephant. Scientific Reports. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-02192-4