Humanitarian remoteness: aid work practices from 'little Aleppo'

The distance between humanitarian organizations and populations with urgent needs only grows. Until 2001, NGO and United Nations workers were respected, their t-shirts logos were a symbolic reference in any emergency. However, the "war on terror" and increased securitization at all levels, has produced a growing sense of insecurity in intervention areas, fueled by a withdrawal of organizations and their international workers towards safer spaces. It is already common to manage humanitarian operations at a distance, relying on new technologies to operate remotely, which implies an unequal division of labor because the risk is transferred to people who work locally risking and losing their lives in order to help their compatriots.

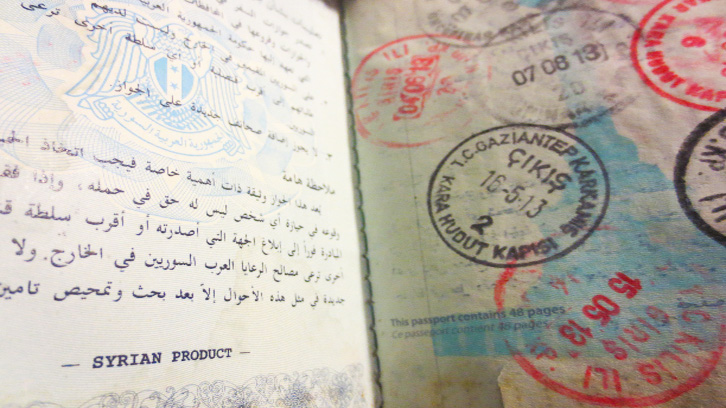

This research, after two years (2015-2016) of ethnographic fieldwork in Gaziantep, analyzes remote management of humanitarian intervention for northern Syria across the border with Turkey and shows how humanitarian personnel maintain the illusion of being in control, while operating through organizations and workers who assume all risks in this dangerous context. “Humanitarian remoteness” set of remote practices embedded in historical, political and economic relations within the humanitarian transnational social field, where international aid workers and organizations not only grapple with the challenges presented by no-go areas but constantly re-create remoteness through daily aid praxis. It helps us to understand how we socially and culturally imagine people who suffer in distant places and how they must be assisted following the humanitarian principles (neutrality, humanity and impartiality). In this case, the organizations’ offices are in Gaziantep, a twin Turkish city of Aleppo (Syria), which is located on the other side of the nearby border.

Across the border that separates the horrors of war from the Turkish "calm", workers and their organizations operate relying on new technologies, but recognizing that direct intervention is necessary to send all kinds of assistance to the millions of displaced, injured and besieged people since the beginning of the conflict in 2011.

Frustration over the magnitude of needs, the difficulty of operating remotely and the uncertainty of not knowing if humanitarian aid reaches those who need it most, is not preventing the humanitarian remoteness and its practices from being recognized as legitimate in this and other interventions.

References

Fradejas-García, I. (2019). Humanitarian remoteness: aid work practices from ‘little Aleppo’. Social Anthropology, 27(2), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12651