Less ants means more aphids!

Ant-aphid interactions are well know to growers and scientists. Ants feed on the honeydew excreted by aphids and aphids are protected from predators and parasited by the ants. We conducted a five-year experiment of ant-exclusion from the canopies of citrus trees from an organic grove at La Selva del Camp (Tarragona) as a possible method of biological control of aphids. We excluded ants by applying a sticky substance on the tree trunk. Insects and spiders from the canopies were sampled monthly. Aphid numbers were noted as well. We expected trees with free access of ants to have higher aphid attack levels and those ant-excluded trees to have aphid levels checked by natural predators and parasites. However, our results were surprising: the exclusion of ants from the canopies increased, instead of reducing, aphid abundance.

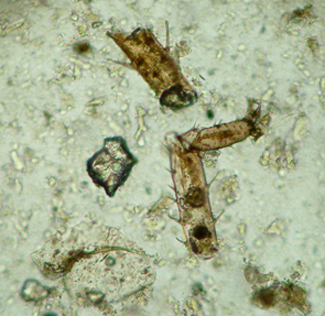

To explain this unexpected result, we reasoned that the exclusion of ants from the canopies might also have excluded other crawling insects that prey on aphids, such as the European earwig (Forficula auricularia). When dissecting captured earwigs we detected aphid remains in their gut, closely tracking the presence of aphids in the field. Such a possibility is supported by the negative relationship between aphid density and the abundance of earwigs, consistent with a top-down control of aphids by earwigs. In contrast, the abundance of other aphid predators (ladybirds, bugs and neuroptera) had no such negative effect on aphid density but a positive one, suggesting a bottom-up control, and showed no differences between control and ant-excluded trees. Thus, the most likely explanation for the increase in aphid abundance in the ant-excluded trees is the absence of earwigs from the canopies of the experimental trees, providing further evidence of the major role that earwigs play as control agents of aphids in cultivated trees.

Our results add support to what is already known of the role of earwigs as important aphid predators in fruit orchards in temperate regions of Europe, United States, Australia, and New Zealand. Earwigs, being generalist predators that feed not only in aphids but other pests and being almost globally distributed, have a role as a pest controller in organic agriculture or integrated fruit production which deserves further attention. However, earwigs can become pests themselves in some instances, as in soft-fleshed fruits and even in apples, by extending damage from previous cuts.

References

"Effects of the concurrent exclusion of ants and earwigs on aphid abundance in an organic citrus grove". Piñol, J., Espadaler, X., Cañellas, N., & Pérez, N. Biocontrol 54(2): 515-527, 2009.